Below you’ll find the (slightly revised) text of a talk I held on 23 January 2014 at the Netherlands Institute Turkey on Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar and his novel ‘Huzur’ (‘A mind at Peace’).

The translators among you will probably agree with me that after spending several months wandering around in a text one can easily end up cherishing the illusion that the world you happen to be emerged in must be known to everyone else as well. The universe of that particular novel becomes so much of a second home that it is difficult to imagine other people might not inhabit that world. Admittedly, it’s a weird illusion. I assume that not all of you have read Tanpınar’s novel Huzur which in English is called ‘A Mind at Peace’, and ‘Sereen’ in my Dutch translation.

The translators among you will probably agree with me that after spending several months wandering around in a text one can easily end up cherishing the illusion that the world you happen to be emerged in must be known to everyone else as well. The universe of that particular novel becomes so much of a second home that it is difficult to imagine other people might not inhabit that world. Admittedly, it’s a weird illusion. I assume that not all of you have read Tanpınar’s novel Huzur which in English is called ‘A Mind at Peace’, and ‘Sereen’ in my Dutch translation.

Tanpınar is no doubt one of the best known modern authors in Turkey, a writer who enjoys a high literary prestige. His novel Huzur is also widely known, although not many people have actually read the book. But it’s also true that for a long period Tanpınar was considered a conservative writer, someone who was not particularly popular among the progressive (literary) establishment – I’ll come back to that in a minute. In addition, to many young readers in Turkey today the Ottoman culture Tanpınar refers to so abundantly in Huzur is a far, exotic and foreign world. Huzur is therefore not an easy read, also not for Turkish readers. But as several Dutch critics remarked when the Dutch translation came out a year ago: even though reading Huzur requires an effort, in the end you do get something in return. Maybe we best start with a short summary of the novel.

Summary

Huzur is many things but to give you a general idea, it is also the story of the tragic love between Mümtaz and Nuran. The novel is made up of four parts, all of them named after one of the main characters. Despite the length of the novel, the story takes place in a time span of only twenty four hours, in one single day: It is the 31st of August 1939, the day before the outbreak of the Second World War. However, the many flashbacks and memories woven into the novel – Tanpınar was an admirer of James Joyce and Marcel Proust – stretch the boundaries of this single day to a time span of many years.

Huzur starts with Mümtaz walking the streets of Istanbul. He has to run several errands for his cousin İhsan who is tied to his bed because of a severe case of pneumonia. While walking through the city Mümtaz thinks of his childhood remembering the death of his parents during the War of Independence and the time he went to live with İhsan and his wife Macide in the old part of Istanbul on the historical peninsula. İhsan is more than just a relative, to Mümtaz he’s also a mentor, his teacher. İhsan introduces Mümtaz to Ottoman history, together they discuss the political situation in Turkey, the war at hand – and war preparations are going on on every street Mümtaz passes. But Mümtaz also thinks of his relationship with Nuran, which has come to an end because Nuran decided to reconcile with her former husband.

The second part of the novel is called after Nuran and takes us back a year to the spring of 1938, when the love between Mümtaz and Nuran is about to blossom. Their romance which started in spring follows the same course as the seasons on the shore of the Bosporus. Mümtaz had left the banks of the Golden Horn to go and live in the village of Emirgân. Unlike today, in the thirties the shores of the Bosporus were still two green strips of land, spotted with isolated villages and the wooden summer residencies of well-off families. It’s a world far from the city centre in Taksim. They go for long walks on the shores, and for rowing trips on the water. Slowly, they start to make plans for a future together. But the end of summer spreads a sense of doom and foreboding in their relationship.

And in the third part of the novel, which is called ‘Suat’, things do indeed go wrong. Suat is related to Mümtaz and in all respects his opposite. He looks down on women. He’s a nihilist and he slams everything that’s old-fashioned and not modern. When Mümtaz and Nuran organise a dinner party with a concert of Ottoman classical music Suat ruins the evening. He suffers from tuberculosis and will probably die soon but meanwhile he makes it his mission to destroy Mümtaz’ and Nuran’s relationship. At the end of the summer Nuran’s family moves to Taksim, and Mümtaz rents a small apartment close by. He and Nuran want to get married, but Nuran also feels obliged to reconcile with her former husband. Mümtaz feels in limbo, waiting for his love to make up her mind. When she finally agrees to marry him, Suat decides to commit suicide in the hallway of Mümtaz’ apartment. Nuran breaks off their relationship. In her opinion there’s no chance they will ever be happy together. She leaves the city for Bursa, then carries on to Izmir to start a new life with her former husband and her little daughter. Mümtaz stays behind feeling heart-broken and at a complete loss.

In the final part, which is called ‘Mümtaz’, we’re back in August 1939, the day before the outbreak of World War II. İhsan’s health has deteriorated and Mümtaz goes out to fetch a doctor. When they come back, İhsan appears to be in a slightly better state. Mümtaz leaves again for medicine. When he returns, he collapses on İhsan’s doorstep. In a semi-conscious state he fights Suat telling him that he won’t commit suicide like he did and that he will carry the burden of life. When he finally enters the house, Hitler has just given the order to attack.

A novel about Istanbul

As can be seen from this short summary Mümtaz is not exactly someone who spends a lot of time at home. Quite the opposite: He is permanently on the move and as a result the city of Istanbul is present on nearly every page of the novel. Very much like Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom who roam the streets of Dublin in James Joyce’s Ulysses, Tanpınar’s protagonist Mümtaz covers big parts of the city he lives in. While writing Huzur in the forties of the last century, Tanpınar also lived in Istanbul, in the district of Kadıköy on the Asian shore where the Bosporus flows into the Sea of Marmara. And Tanpınar knew his home town well.

As can be seen from this short summary Mümtaz is not exactly someone who spends a lot of time at home. Quite the opposite: He is permanently on the move and as a result the city of Istanbul is present on nearly every page of the novel. Very much like Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom who roam the streets of Dublin in James Joyce’s Ulysses, Tanpınar’s protagonist Mümtaz covers big parts of the city he lives in. While writing Huzur in the forties of the last century, Tanpınar also lived in Istanbul, in the district of Kadıköy on the Asian shore where the Bosporus flows into the Sea of Marmara. And Tanpınar knew his home town well.

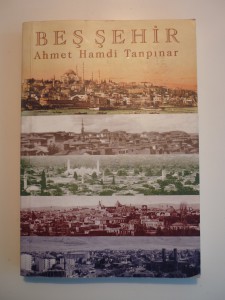

But then, there are many cities in Turkey Tanpınar knew well. As the son of a judge he lived in places as different as Sinop, Siirt and Antalya. As a teacher of Turkish literature he worked in Ankara, Erzurum and Konya. His travels were complemented by his historical and cultural interest in his country and the vast knowledge he amassed over the years. All of that resulted in a collection of essays called Five cities (‘Beş şehir’), a book about the five different capitals of the Ottoman Empire and the continuity between the various civilisations that were rooted in these cities.

So, one wonders, is it mere coincidence that the novel Huzur is set in Istanbul? Is the choice of Istanbul simply due to the fact that the author happened to live there when he started writing the novel? Is Istanbul, in other words, a random choice of scenery? And could Huzur just as well have been located in one of the many other cities in Turkey? In Bursa, for instance? In Konya? Or in Edirne?

For readers who know that Tanpınar was a scholar of Ottoman history and very much involved in the issues of East and West, of tradition and modernity, and also for those who are familiar with Istanbul’s history, Mümtaz’ walks and rowing trips are not just wanderings on the off chance. If we have a closer look at how exactly Mümtaz moves through the city, we will notice that the Istanbulian neighbourhoods do not serve as a mere décor. On the contrary, Tanpınar skillfully uses the city’s historical layout to show us something else.

In 1938, the year in which Mümtaz falls in love with Nuran, fifteen years had passed since Istanbul had stopped being a capital. With the proclamation of the Turkish republic in 1923, Ankara replaced Istanbul, the city which had been the capital of the Ottoman Empire for almost 500 years. It was only one of many steps Atatürk and his followers, the Kemalists, decided to take in order to turn the Ottoman past into a closed book.

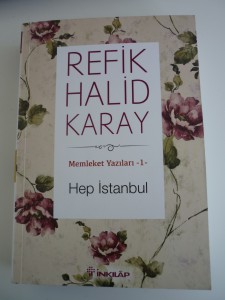

As is often the case with common knowledge, one tends to forget the actual implications of such measures. Or let me speak for myself, I never actually realised the impact this decision had on Istanbul until I read a text written by my friend and colleague Tuncay Birkan. For some years now, Tuncay Birkan has been busy tracking a huge amount of lost articles written by Refik Halid Karay, another of Turkey’s prominent authors. Karay and Tanpınar were contemporaries. This collection of articles written by Karay for newspapers and magazines will be published in 18 volumes. The first two came out just last week.

In his preface to the first volume which is dedicated to Istanbul, Tuncay Birkan points out how for the new Kemalist regime Istanbul was a synonym for the past, whereas Ankara stood for the present and the future. With its many visible features reminiscent of the religious and cosmopolitan Ottoman past, Istanbul was thereby turned into Ankara’s ultimate ‘other’. The new capital was to become nationalist, contemporary and secular in order to represent the new ideals.

In his preface to the first volume which is dedicated to Istanbul, Tuncay Birkan points out how for the new Kemalist regime Istanbul was a synonym for the past, whereas Ankara stood for the present and the future. With its many visible features reminiscent of the religious and cosmopolitan Ottoman past, Istanbul was thereby turned into Ankara’s ultimate ‘other’. The new capital was to become nationalist, contemporary and secular in order to represent the new ideals.

In addition, the images that were created for the old and the new capital soon took on a moral dimension as well. This may have been facilitated by the double meaning of the Turkish word ‘temiz’ meaning both ‘clean’ and ‘decent’. From the dust and dirt of ages that were felt to cover Istanbul it was only a small step to endowing it with a character which wasn’t decent. Ankara’s brand new wide and straight boulevards, on the other hand, were associated with being straight forward and open minded. Thus, whereas Istanbul came to be identified with the traditions of the Ottoman Empire and the sultans’ family, with cosmopolitan pollution and degeneration, Ankara became the symbol of purity, moral superiority and idealism.

This was more than the hollow rhetoric of men who had just come to power. It directly affected the allocation of state budgets for housing and public works. In the first Five-Year-Plan for the development of the country the budget for public works in Istanbul was staggeringly low when compared to the budgets available for Ankara and other much smaller towns in Anatolia. With hardly any money to spend, the former capital started to fall into disrepair: there was a lack of drinking water, the infrastructure was in no way capable of meeting transportation needs, historical buildings were neglected or disappeared behind clusters of barracks and ramshackle sheds, public transport was carried out by slow busses and streetcars and dilapidated ferries. In other words, the Kemalist government in Ankara resorted to a deliberate, ideologically charged policy of neglect. As the sociologist Hakan Kaynar puts it: ‘Rather than making itself visible in Istanbul, the republic preferred to make Istanbul and its past invisible.’

In 1938, the year before the story of Huzur takes place, the author Refik Halid Karay was allowed to return to Istanbul after fifteen years in exile. According to a well known anecdote, soon after his arrival in his sorely missed city, Karay who was known for his biting pen, was summoned to a police station. There he was told not to even think about writing an article with the title ‘Miserable Istanbul’. It shows how pitiful the city had become, and how much the state was aware of the results of its policy.

When we look at Huzur from this perspective, Tanpınar’s choice of Istanbul and the book’s reminders of the Ottoman past were indeed a statement and a direct reference to the dominant political discourse in the thirties and forties. But as the former capital of the Ottoman empire and the ultimate ‘other’ of the young republic’s new capital, Istanbul was the city of choice to write a novel about the country’s past and its relationship to its present and future as well as about the debate on tradition vs. modernity.

The country’s past, present and future are not only present in the storyline of the novel but also in the many political discussions by its protagonists and not least in the areas and neighbourhoods chosen by Tanpınar as a location for Mümtaz’ lodgings and walks.

Huzur starts on the historical peninsula, south of the Golden Horn. The house where İhsan and Macide live, Mümtaz’ new home when he arrives in the city, is located in the oldest part of Ottoman Istanbul. When Mümtaz leaves home after finishing school, he moves from the historical peninsula to the northern part of the Bosporus, to the village of Emirgân. His beloved Nuran lives right across from him – on the Anatolian shore, in a mansion in the village of Kandilli. Together they go for rowing tours on the Bosporus, just as the well-off Ottomans used to do in the Empire’s cultural Golden age. When winter sets in, first in the city and soon after in their relationship, they move to Taksim, the modern city centre by Kemalist standards. In the novel’s last part, Mümtaz is back with İhsan on the Ottoman peninsular. Thus, Mümtaz’ respective residencies in the city represent the development of both the Ottoman Empire and Turkey: from the old Ottoman part on the Golden Horn to the Bosporus and the Ottoman Golden Age and eventually to Taksim, the symbol of the new republic.

The final part reads like an afterword: When Mümtazgoes back to the historical peninsular after Nuran has left him, it feels like an attempt to come to terms with the past, to say good-bye and to make up his mind about the future. The novel’s focus is on the contrast between the Bosporus, the place where Mümtaz and Nuran first fall in love, and Taksim, where their love comes to such a tragic end.

Tanpınar depicts the Bosporus as a homogeneous and secluded environment, the scenery for a refined culture – the ‘Bosporus civilisation’ as it was called by one of Tanpınar’s friends, the author Abdülhak Şinasi Hisar. This ‘Bosporus civilisation’ goes back to the seventeenth and eighteenth century when the Ottoman elites left the shores of the Golden Horn and started to build their summer residencies on the banks of the Bosporus. Ottoman culture, the music by composers such as Dede Efendi and divan poetry by poets like Bâkî and Nedim played an important role. It was a culture in which tradition was more important than modernism, in which the work of art had greater significance the artist and in which modesty was considered more important than being visible as an individual. At the same time it was a secluded culture. Not only in a practical sense: when Tanpınar wrote Huzur there were no roads connecting the villages along the shores. In a social sense access to the world of the yalı’s, the villas on the waterfront, was at least as restricted. It was a universe in its own right, one that was so little subject to change that time seemed to have come to a standstill, a world so secluded that even the light seemed to glow from its inner self, from within the dark foliage of the trees and the depths of the water.

Tanpınar depicts the Bosporus as a homogeneous and secluded environment, the scenery for a refined culture – the ‘Bosporus civilisation’ as it was called by one of Tanpınar’s friends, the author Abdülhak Şinasi Hisar. This ‘Bosporus civilisation’ goes back to the seventeenth and eighteenth century when the Ottoman elites left the shores of the Golden Horn and started to build their summer residencies on the banks of the Bosporus. Ottoman culture, the music by composers such as Dede Efendi and divan poetry by poets like Bâkî and Nedim played an important role. It was a culture in which tradition was more important than modernism, in which the work of art had greater significance the artist and in which modesty was considered more important than being visible as an individual. At the same time it was a secluded culture. Not only in a practical sense: when Tanpınar wrote Huzur there were no roads connecting the villages along the shores. In a social sense access to the world of the yalı’s, the villas on the waterfront, was at least as restricted. It was a universe in its own right, one that was so little subject to change that time seemed to have come to a standstill, a world so secluded that even the light seemed to glow from its inner self, from within the dark foliage of the trees and the depths of the water.

In this respect the Bosporus is the exact opposite of Taksim – the district which for centuries had been open to foreign influences, and especially to the influence of European culture. From an early age on the merchants, artists and ambassadors from Europe settled in this part of the city which was then called Pera. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth century reformist Ottomans started to swap their villas on the Bosporus for an apartment in modern, European oriented Taksim: a part of the city which was not submerged in the silence of the centuries, but buzzing with theatres and cafés and the frantic life of business and trade.

Music and time

The cultural contrasts exemplified by the parts of Istanbul Tanpınar chose as a setting for his story, are mirrored in music. Mümtaz’ walks through the city are very often accompanied by musical compositions: classical Ottoman music, but also songs from the nineteenth century and traditional folk songs. The music coming to Mümtaz’ mind is evoked by the historical buildings he sees on his way. It changes Istanbul’s landscape into ‘a map of melodies, of dream images’ as Tanpınar puts it. The melodies on the map connect the different places to each other and to history. In this respect, the Ottoman compositions and songs are almost like songlines, or dreaming tracks as they were called by Bruce Chatwin in his well-known book about aboriginal creation myths in Australia.

In Huzur Tanpınar also contrasts Ottoman music with Western classical music. A dinner party given by Mümtaz at his house on the shore of the Bosporus, is followed by a concert of Ottoman classical music. Yet, when Suat decides to commit suicide in the Taksim apartment he first sits down to listen to some music. Instead of a record by Dede Efendi he chooses a violin concert by Beethoven. In Tanpınar’s view this discord in music represents a more encompassing cultural issue. Istanbul is coined by two cultures, in Tanpınar’s words by two civilisations. The question is how the two should be related to one another.

But there’s still more to say about Huzur and music. Huzur not only quotes the musical compositions going through Mümtaz’ mind but the structure of the novel itself bears similarities with a musical composition. With Mümtaz’ voices being simultaneously in the present and in different periods of the past, the novel is a piece of music in its own right. Not a piece of Ottoman music for one voice, but a polyphonic symphony by Beethoven or Wagner.

With every new voice added to the novel, time is stretched a little more. Music ís time. In Mümtaz’, or Tanpınar’s words:

[Muziek is geen goed voertuig voor de liefde… dacht hij.] Want muziek werkt op de tijd. Muziek is de ordening van de tijd. Ze vernietigt het heden. [Terwijl geluk zich juist in het heden bevindt.]’

‘[Music is not a good medium for love’ he thought.] ‘Because music has an effect on time. Music structures time. It destroys the present. [Whereas happiness takes place in the moment].’ [p.357]

Just as life itself, a musical composition is confined in length. Only the elevator music played in shopping malls and supermarkets can go on forever. Any other composition ultimately grows silent. And just as life itself, music not only has a length, but also a width: Perhaps one could describe it as the sum of tones you hear simultaneously. Yet, no matter how confined a composition may be in length, the width of music, and thus the width of time, can be stretched infinitely. The polyphony of a musical composition, or of a novel like Huzur, is a way of ‘leven in de breedte’ to use a term coined by the Dutch novelist A.F.Th. van der Heijden, which could be translated as leading a life which stretches the width of the moment.

In other words, in Huzur music is not only connected to space, but also to time. More than that: place is time. With their architectural characteristics the magnificent old buildings, the historical mosques, the public baths encountered by Mümtaz on his walks and rowing trips not only refer to a certain historical time or era. Due to their capacity of evoking music and the memories associated with it, they are time, curdled time, solidified time. Substance that is, something which enables us to re-experience a past moment or period over and over again. This idea of space and objects as solidified time may sound familiar to the readers of Orhan Pamuk’s last novel. In The Museum of Innocence (‘Het museum van de onschuld’ as it is called in Dutch) the protagonist Kemal eagerly collects objects that have been touched by Füsun, his unattainable love. The end of a cigarette, a hair pin, tens of small dog shaped figurines. They are chunks of solidified time, a substance which allows Kemal to re-experience the time he spent in her presence. They are exhibited in the museum Kemal dedicates to his beloved.

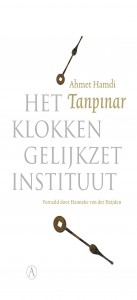

In Tanpınar’s work time is a key concept. In his other famous novel: The Time Regulation Institute (‘Het klokkengelijkzetinstituut’) it is even included in the title. This novel was published in 1954 , five years after Huzur. It first came out as a series in a newspaper and as a book in 1961, only two months before Tanpınar’s premature death (for those who want to read it in English: a new translation by Alexander Dawe and Maureen Freely was just published by Penguin). The Time Regulation Institute is about an institute which is established with the aim of regulating all the clocks in the country. Quite contrary to Huzur, it is written in a freewheeling and ironical style. The stylistic differences between these two novels are so big that most readers in Turkey either like Huzur or The Time Regulation Institute. Readers who are a fan of both are rare. But no matter how much these two novels may differ in tone, thematically they are closely related: both of them are about time, the essence of time and the way it is experienced.

In Tanpınar’s work time is a key concept. In his other famous novel: The Time Regulation Institute (‘Het klokkengelijkzetinstituut’) it is even included in the title. This novel was published in 1954 , five years after Huzur. It first came out as a series in a newspaper and as a book in 1961, only two months before Tanpınar’s premature death (for those who want to read it in English: a new translation by Alexander Dawe and Maureen Freely was just published by Penguin). The Time Regulation Institute is about an institute which is established with the aim of regulating all the clocks in the country. Quite contrary to Huzur, it is written in a freewheeling and ironical style. The stylistic differences between these two novels are so big that most readers in Turkey either like Huzur or The Time Regulation Institute. Readers who are a fan of both are rare. But no matter how much these two novels may differ in tone, thematically they are closely related: both of them are about time, the essence of time and the way it is experienced.

As an adept of the French philosopher Henri Bergson, Tanpınar considers time to be a solid, uninterrupted stream – a stream which is generated by humans, by every single individual. Time owes its existence to human memory and its capacity to recreate the past again and again. Without this permanent process of reinventing the past, the future simply wouldn’t exist. This implies that by cutting off the past we cut off the future as well. And this is not only true for individuals and their relation to the past, but also for society as a whole. In Tanpınar’s view denial of the Ottoman cultural heritage is therefore bound to lead to nothing. Reforms which are adopted from the West yet lack any substrate in Turkey are destined to fail. You can’t take on another culture the way you put on a new shirt. Instead, the past should be integrated in both the present and the future: the Ottoman past as an integral part of the modern republic designed along western lines. Or, in the imagery of Huzur: an Ottoman motive in a Western symphony.

To us, readers in the 21st century – and this could be especially true for readers from outside of Turkey – the concept of a continuum of time may seem somewhat self-evident. But in Turkey at the beginning of the 20th century Tanpınar’s concept of time and history was not exactly common sense. Tanpınar, who was a specialist in Ottoman literary history, saw with his own eyes how the political and ideological climate in his country changed, and how the door to the past was eventually firmly shut. As a teenager he witnessed how the Ottoman Empire became a shadow of its former mighty self. When he was in his twenties, he heard the proclamation of the republic of Turkey which was to replace it. In his thirties Tanpınar was surrounded by the zeal of Atatürk’s followers in trying to implement their ideals for the future. And in his forties and fifties he lived among the increasing numbers of critical voices raised to express their disappointment. Throughout the years Tanpınar spent writing, the past was systematically wiped out from public life. It was expected of artists and authors to propagate the new ideals of the republic either with a certain amount of enthusiasm, or to at least be engaged with the future. Tanpınar’s interest in the Ottoman past didn’t earn him a lot of approval and was even considered suspicious. His fiction was often thought of as being reactionary, food for conservative and religious circles, for people who didn’t want to have anything to do with Kemalist reforms.

It’s only in the last two decades that this image has started to change. Today, Tanpınar is considered an author who wanted to stay in touch with the influences of two major cultures, with ‘the East’ and ‘the West’ as they’re often labeled. Since the increasing recognition of the influences of both these cultural spheres, Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar has become one of the icons of modern Turkish literature. This is not only due to the fact that times have changed. In part Tanpınar owes his new status also to his younger colleagues, Turkish authors who refuse, just as he did, to commit to a single ideological camp but instead, make Turkey’s cultural discord their topic. Oğuz Atay, the author of the novel Tutunamayanlar [‘The Disconnected’] which ridicules Kemalism among many other political ideologies, is one example. Orhan Pamuk is another. I already mentioned that in The Museum of Innocence Pamuk was inspired by Tanpınar’s idea of substance as solidified time. Mümtaz’ walks through Istanbul are echoed in Pamuk’s novel The Black Book, in which the protagonist Galip goes for endless walks in Istanbul in search of his wife Rüya. Pamuk never made a secret of his admiration for Tanpınar, neither in his novels nor in his interviews.

Fleuve

In Tanpınar’s work the concept of a synthesis, of an uninterrupted continuum is not restricted to time. In his fiction the boundaries between thought and speech vanish, lines between different disciplines of art become blurred, different sensory perceptions blend into one: a novel can at the same time be a musical composition, sounds can have colours. And outside the realm of Huzur, in the wider context of the body of work left behind by Tanpınar, literary genres seem to merge too. Tanpınar’s oeuvre is not confined to novels. He also wrote short stories, and poems, he’s the author of a famous literary history, he wrote essays like his Five cities, and studies and reviews of other disciplines such as the theatre, sculpture, and of course, music.

In Tanpınar’s work the concept of a synthesis, of an uninterrupted continuum is not restricted to time. In his fiction the boundaries between thought and speech vanish, lines between different disciplines of art become blurred, different sensory perceptions blend into one: a novel can at the same time be a musical composition, sounds can have colours. And outside the realm of Huzur, in the wider context of the body of work left behind by Tanpınar, literary genres seem to merge too. Tanpınar’s oeuvre is not confined to novels. He also wrote short stories, and poems, he’s the author of a famous literary history, he wrote essays like his Five cities, and studies and reviews of other disciplines such as the theatre, sculpture, and of course, music.

We could relate this to a mystical experience in which the whole world is felt to be one undivided whole and the individual as a mere drop in the ocean of time. This is exactly what Mümtaz and Nuran experience on the shores of the Bosporus when they listen to the Prelude in Ferahfezâ, a composition by the Mevlevi composer Dede Efendi. This is at the same time one of the key scenes in the novel.

In this sense, it is telling that Tanpınar conceived his novel as a roman fleuve – a ‘river novel’ as it translates literally – an idea to which he was inspired by the French novelist Marcel Proust. Huzur was actually the second novel in a trilogy, however, things didn’t work out exactly the way Tanpınar had intended. Today, the first novel, Tanpınar’s debut Mahur Beste [‘Composition in Mahur’] and his third novel, Sahnenin dışındakiler [‘Those off-stage’] are known to just a very small group of readers. Huzur is the only book of the trilogy with a still fairly large readership, and it is increasingly translated into other languages.

References

Atay, Oğuz, Tutunamayanlar. Istanbul, 1971/1972.

[Dutch translation] Het leven in stukken. Amsterdam: Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2011. Translated by Margreet Dorleijn & Hanneke van der Heijden.

Chatwin, Bruce, The Songlines. London: Franklin Press, 1986.

Heijden, A.F.Th. van der, De tandeloze tijd. Amsterdam: Querido / De Bezige Bij. [Series of novels, still to be continued, the first of which was published in 1983]

Karay, Refik Halid, Hep İstanbul. İstanbul: İnkılap, 2014. Compiled and edited by Tuncay Birkan.

Kaynar, Hakan, Projesiz Modernleşme: Cumhuriyet İstanbul’undan Gündelik Fragmanlar. İstanbul: Pera Müzesi Yayınları, 2012.

Pamuk, İstanbul. Hatıralar ve Şehir. İstanbul: Yapı Kredi, 2003.

[Dutch translation] Istanbul. Herinneringen en de stad. Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers / De Bezige Bij. Translated by Hanneke van der Heijden.

[English translation] Istanbul. Memories and the City. New York: Vintage, 2006. Translated by Maureen Freely.

Pamuk, Orhan, Kara Kitap. İstanbul, İletişim, 1990.

[Dutch translation] Het zwarte boek. Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers / De Bezige Bij. Translated by Margreet Dorleijn.

[English translation] The Black Book. New York: Vintage. Translated by Maureen Freely.

Pamuk, Orhan, Masumiyet Müzesi. İstanbul: İletişim, 2008.

[Dutch translation] Het museum van de onschuld. Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 2009 / De Bezige Bij, 2012. Translated by Margreet Dorleijn.

[English translation] The Museum of Innocence. New York: Knopf, 2009. Translated by Maureen Freely.

Tanpınar, Ahmet Hamdi, Beş şehir. İstanbul, 1946.

Tanpınar, Ahmet Hamdi, Huzur. Istanbul, 1949.

[Dutch translation] Sereen. Amsterdam: Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2013. Translated by Hanneke van der Heijden.

[English translation] A Mind at Peace. New York: Archipelago, 2008. Translated by Erdağ Göknar.

Tanpınar, Ahmet Hamdi, Mahur Beste. İstanbul, 1944.

Tanpınar, Ahmet Hamdi, Saatleri Ayarlama Enstitüsü. İstanbul, 1961.

[Dutch translation] Het klokkengelijkzetinstituut. Amsterdam: Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep, 2009. Translated by Hanneke van der Heijden.

[English translation] The Time Regulation Institute. New York: Penguin, 2014. Translated by Maureen Freely & Alexander Dawe.

Tanpınar, Ahmet Hamdi, Sahnenin dışındakiler. İstanbul, [1973].